We are thrilled to be supporting the safe reopening of cinemas and to support them in doing so, we are taking a dive into our catalogue for a closer look at what some iconic films mean to all of us, and why.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of Michael Mann's unforgettable feature film debut, neo-noir action thriller, Thief, Steven Rybin takes a closer look at the 1981 classic.

Thief will be screening at selected cinemas worldwide from June 2021. For more details, please visit our now showing page.

“I am Joe-the-boss of my own body.” So declares jewel thief Frank, played by James Caan, in writer-director Michael Mann’s first major studio film, Thief (1981). That line of dialogue, expressing the character’s steadfast refusal to capitulate to any but his own authority, could be fittingly spoken by any number of Mann protagonists. Frank’s brethren in Mann’s filmography – William Petersen’s obsessed police investigator in Manhunter (1986), Robert De Niro’s introverted criminal in Heat (1995), or Tom Cruise’s nihilistic hitman in Collateral (2004) – express much the same philosophy. And like those men, Frank ultimately finds himself tangled in a web of social and existential obligations that make autonomy and stubborn self-reliance difficult positions to maintain.

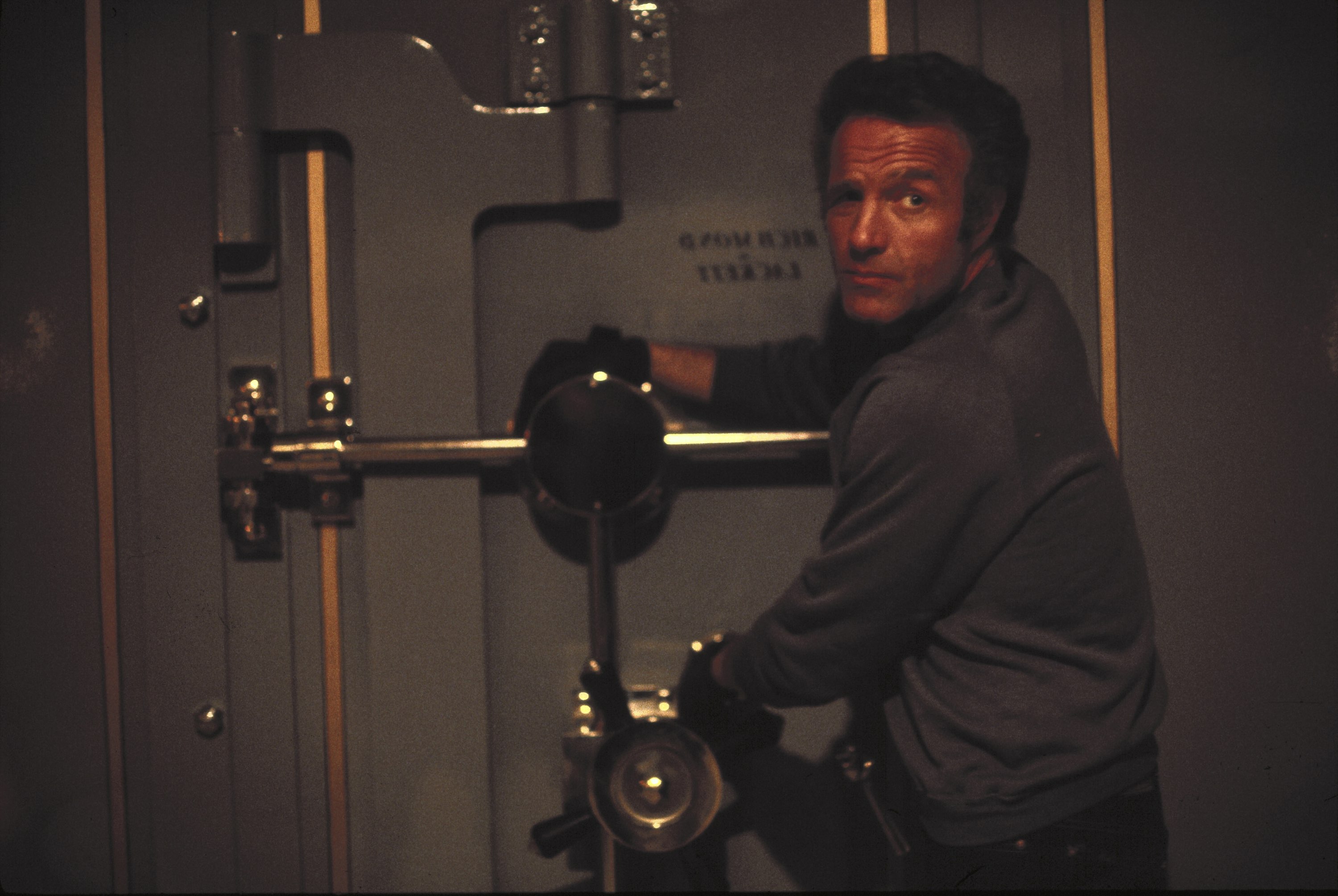

When Thief introduces us to Frank, it is not his relationships with others but rather his distinctive ability to cleanly and quickly crack safes that is underscored. In the opening sequence, Caan’s character is performing a daring jewel heist under the cover of a rain-slicked Chicago night, an efficient operation with a small crew. Although he’s not quite a one-man band – Frank’s pal Barry (James Belushi), a wire-tapper, is one of his crucial collaborators – the film makes clear Frank’s dexterous wielding of tools and technology are the skills that make this criminal operation go. Close-ups throughout the film’s safecracking sequences emphasize Frank’s expert handling of unwieldy instruments and tools as he deftly filches precious materials. Frank’s criminal method is like Thief itself: minimalist and effective. Snatch the jewels, sell them on the street, slip away. He answers to no one but himself.

Mann’s stylish handling of the heist sequences are as impressive as his protagonist’s purloining. But Mann’s images elsewhere suggest a world of city lights and urban spaces beyond any individual’s control. (The director has described his protagonist in Thief as a “rat in a maze.”) The film’s cinematographer, Donald E. Thorin (1934-2016) – a veteran of major studio pictures by other directors including Purple Rain (1984), Midnight Run (1988) and Scent of a Woman (1992) – paints the cityscapes of and surrounding Chicago both as reflections of and potential obstacles to Frank’s dreams. Early in the film, Frank enjoys a rare, peaceful moment with a fisherman friend on a dock in the city, with Mann’s and Thorin’s framing of the horizon line suggesting Frank’s hopes for a future beyond the nighttime spaces where he performs his thievery. Frank’s ambitions are also materialized in a collage of photographs that he keeps in his pocket – mostly cut-outs from magazines – that represent his own version of the American dream. A specific image is of Okla (Willie Nelson), a close friend from Frank’s time in prison, to whom the thief remains loyal; his efforts to have Okla pardoned from his sentence form one of the film’s subplots. Other images are more archetypal: romance, marriage. Frank’s hope for the latter is dependent on Jessie (Tuesday Weld), a cashier with whom he has an ongoing, and at times contentious, romantic relationship. She wants to go slow, but for Frank, as for many Mann protagonists, time is luck. He’s already lost too much of it in prison, and he doesn’t want to waste it.

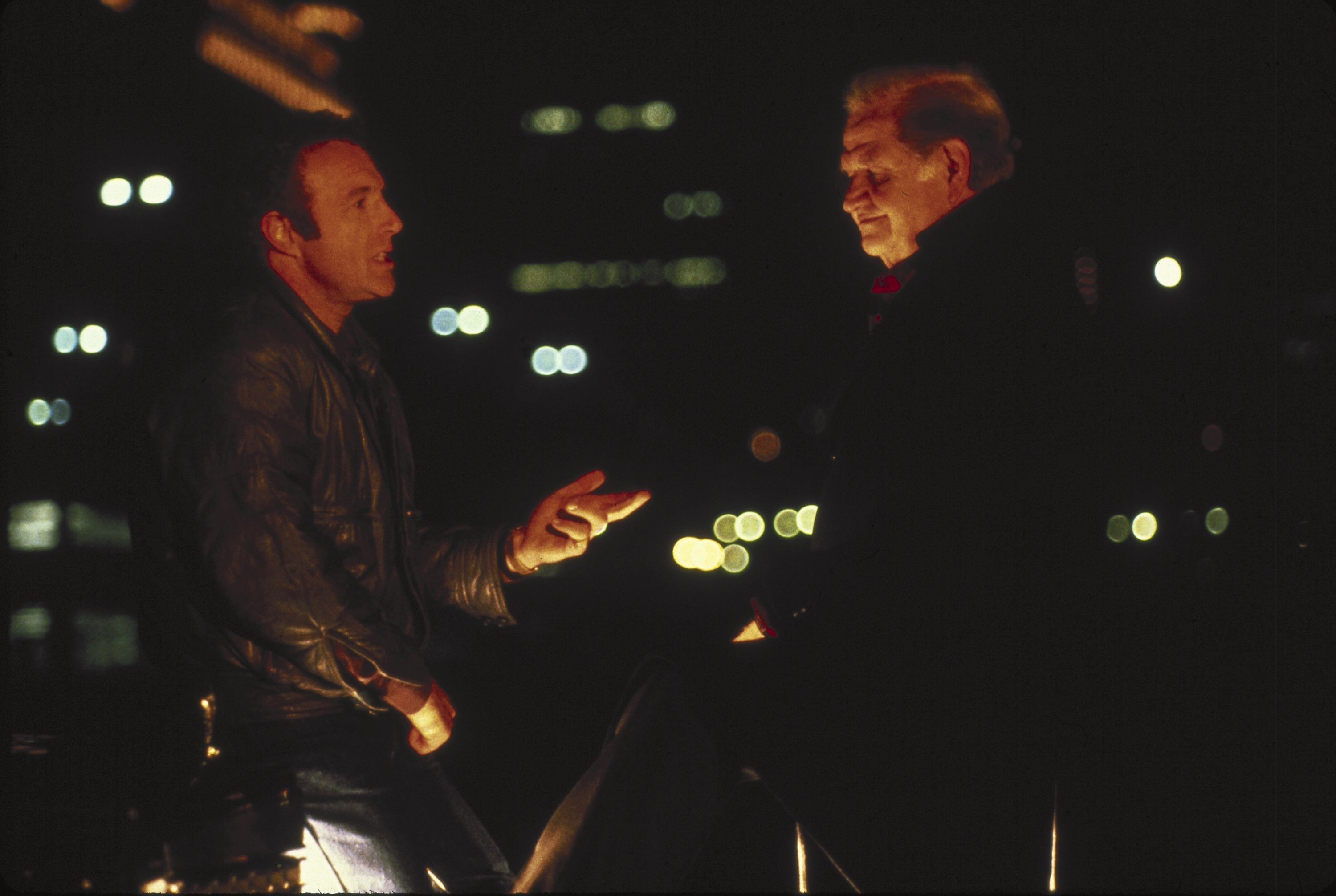

Yet the city streets and alleys of Chicago are often presented by Mann and Thorin and something beyond Frank’s grasp, especially evident in a nighttime sequence midway through the film in which Frank fatefully meets with crime boss Leo (Robert Prosky) against the backdrop of the cityscape. Frank is being doubly surveilled here, not only by Leo’s men but also by the cops, who are staking out this meeting between two master criminals. Leo, something of an overseer of various criminal operations, has the connections to get Frank the biggest “scores,” or heist jobs, in the business. If working with Leo gives Frank the opportunity to nab the biggest bounty of his life, it also means giving up some of measure of autonomy and control over his work. In making this deal with Leo, Frank’s autonomy and self-reliance are put to a violent test.

This new restoration of Thief gives contemporary viewers a rare chance to see Mann’s most important early work on the big screen. Compared to the monumental scope of many later Mann films – the sweeping forest and mountain vistas of The Last of the Mohicans (1992), the epic canvas of concrete and glass in the Los Angeles of Heat (1995), and the historical backdrops of Ali (2001) and Public Enemies) (2009) – Thief looks relatively minimalist, and could at first glance be ( mistaken for only an admirable, embryonic work containing motifs and themes that would be deepened later in its director’s career. Yet another viewing confirms that this is one of Mann’s most satisfying films, and one of the best thrillers of the 1980s. Thief seems, relative to Mann’s cinema as a whole, content with a stripped-down, to-the-point aesthetic: it’s a character study. Mann’s later films, of course, study character, but the social webs in which those characters live get vaster and vaster, and more and more abstract, as the films themselves grow stylistically more ambitious. This abstraction is especially evident in a trio of late films, Mann’s “information technology trilogy”: The Insider (1999), Miami Vice (2006), and Blackhat (2015). In contrast to the delicate pointillism of Thief, in that later trilogy the goals of the characters are placed into potentially perilous counterpoint with largely invisible systems of digital, audiovisual technology and surveillance that far outstrip any individual’s autonomy or control.

In Thief, Frank only begins to feel the pressures of such surveillance. In 1981, Mann’s “rat” could still claw his way out of his existential maze using his hands, and his tools, as the film’s violent, melancholic denouement suggests. Mann’s later thieves, it will turn out, are not so lucky.

Steven Rybin is Associate Professor of Film Studies at Minnesota State University, Mankato, USA. He is the author of Geraldine Chaplin: The Gift of Film Performance (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), Gestures of Love: Romancing Performance in Classical Hollywood Cinema (SUNY Press, 2017), Michael Mann: Crime Auteur (Scarecrow Press, 2013), and other books on film.

Whetted your appetite? Thief is available to book on DCP for your cinema or festival - please contact [email protected]

Sign up to our newsletter for more inspiration!