The collective experience of audiences in a cinema watching great films is at the heart what Park Circus is about. We love films, shared stories and escapism, and have asked some of our friends from across the film industry to recommend some of their favourite films for audiences to enjoy as it is safe for cinemas to reopen.

This week, we are celebrating the many brilliant films for children that we are proud to represent, by speaking to Professor Robert Shail, Professor of Film in the Leeds School of Arts at Leeds Beckett University. He has written on children’s cinema and the history of comics including The Children’s Film Foundation: History and Legacy (Palgrave/BFI, 2016) which was supported by the Leverhulme Foundation.

For many people their love for films began when they were first introduced to cinema by their parents or an older sibling; the viewing on offer would invariably be a children’s film. Later on they may have had the pleasure of introducing their own children to classic favourites or experienced the latest variations on the genre designed to appeal to a new generation. Consequently, few cinematic experiences evoke such strong emotional connections as children’s films.

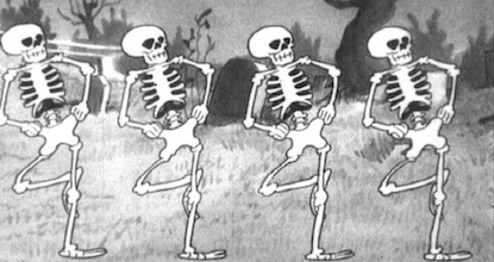

It’s hard to produce a list of children’s films without beginning with Disney. Rather than choose one of their more recent titles or even a classic feature from the 1940s, I have gone back to the company’s earliest days when they were at the forefront of pioneering animation in America. The Skeleton Dance was made in black and white in 1929 as part of the Silly Symphony series. Produced by Walt Disney himself and animated by Ub Iwerks, this is a five-minute gem of visual invention and macabre humour.

The Skeleton Dance (1929)

Digital technology has opened up extraordinary possibilities for animation but compelling storytelling and appealing characters remain as important as ever. Disney/Pixar’s Toy Story (1995) may have been groundbreaking for its use of computer animation but the real heart of the film’s longevity lies in its depiction of friendship. After all, who is going to argue with its request for us all to ‘play nice’.

Animation can come in a vast array of forms and its Japanese version, anime, itself offers everything from challenging adult material to films that evoke the trials and wonders of growing up. One of the most mesmerising is My Neighbour Totoro (1988), created by Miyazaki Hayao for Studio Ghibli. The director’s intentions were apparently to create a drama which was not driven by conflict. Instead we have a dream-like vision of childhood concerns and happiness with unique imagery such as the unforgettable Catbus.

Toy Story (1995)

British cinema has produced its own distinctive approach to children’s animation, nowhere more so than in Watership Down (1978), based on the novel by Richard Adams. Although its drawings are in the Disney mode, this is a film which proves that children’s films can be darkly powerful and deal with complex adult themes. The film aroused controversy from its release and is a far from cosy view of the natural world, but its emotional heft comes directly from the way it honestly confronts death and violence.

An altogether gentler approach can be found in another British film, the perennial favourite The Railway Children (1970), based on the popular novel by E. Nesbitt. Few films can reduce grown adults to tears as efficiently as this tale of an Edwardian family parted from their father who has been unjustly imprisoned. Bathed in summer sunshine and deeply nostalgic, the film builds to a classic finale.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001)

A less reassuring vision of childhood can be found in another British film, The Belles of St Trinian’s (1954), drawn from the cartoons of Ronald Searle. A delight for girls (and boys) of all ages, there has seldom been a more anarchic view of childhood. The horrified reaction of the local population at the return of the girls from their summer break is a wonder to see.

Some mention is also due to the Children’s Film Foundation (CFF), a British organisation dedicated solely to the production of films for children who, for more than thirty years, supplied its sixty-minute features to Saturday film clubs all over the UK, and around the world. Sammy’s Super T-Shirt (1978) is a typical combination of fantasy, adventure, uplifting message, and broad humour.

It’s hard to ignore the huge popularity of J.K. Rowling’s seven-part Harry Potter book series, or its eight-part film franchise. Its spectacular effects and starry casts are a long way from the modest budgets of the CFF, but story and character remain the key ingredients. Later entries are more sombre and thought-provoking but for humour and warmth it’s hard to beat the opening film, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001). And if you enjoy this one, you can proceed to all the others.

The Belles of St Trinian's (1954)

Adventure and wonder have been always been central elements for children’s cinema and, although it was made nearly sixty years ago, Jason and the Argonauts (1963) retains these qualities in abundance. Featuring the magical stop-motion animation work of Ray Harryhausen, the figures of Talos, the Hydra, and - most memorably - the children of the Hydra’s teeth (more skeletons!) are brought vividly to life.

Although not made specifically for children, the comedies of the silent period are a good place to bring this list to a close. There is a playful innocence, along with visual sophistication, to be found in the films of Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, or Laurel and Hardy but I am finishing with Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid (1921), a masterpiece which demonstrates that a mere children’s film can deal with issues of economic deprivation and social injustice whilst being both funny and deeply moving.