We are thrilled to be supporting the safe reopening of cinemas and to support them in doing so, we are taking a dive into our catalogue for a closer look at what some iconic films mean to all of us, and why.

To continue our celebrations around Valentine's Day and to mark Romeo + Juliet's 25th anniversary, Richard Rushton takes a close-up look at acclaimed Australian director Baz Luhrmann.

Baz Luhrmann makes no secret of the fact that love is a central theme in his films. But what kind of love do his films portray? In 1992’s Strictly Ballroom, a romantic couple, Scott and Fran (Paul Mercurio and Tara Morice), exit the film as triumphant and in love, and thus the film delivers a quintessential happily-ever-after ending. And yet, such an ending is rather atypical for Luhrmann’s films. In Moulin Rouge! (2001), for example, even as that film’s guiding motto is ‘The greatest thing you’ll ever know is to love and be loved in return’, we are delivered no happily-ever-after ending. Rather, Satine (Nicole Kidman), the glittering star performer (and prostitute), does not survive at the film’s end: her illness cuts short any happily-ever-after life she might have dreamed of with Christian (Ewan McGregor), the man she has fallen deeply in love with. And then in Luhrmann’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby (2012)), the love affair between Gatsby and Daisy (Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan) ends in tragedy when Gatsby is shot dead. There is no happily-ever-after here. It is therefore worth asking what kind of love we have here.

Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor in Moulin Rouge! (2001)

The model for this kind of love is provided by Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, so it may be unsurprising that Luhrmann directed a stunning adaptation of that play, William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. What version of love does Romeo + Juliet provide? It provides a love that is forbidden, and in the end, a love that is rendered impossible.

This is a very common version of true love: love is at its most intense when it happens in secret, so the fact that Romeo and Juliet are constantly hiding from their parents and the social world that disapproves of their love, is also a key reason why that love takes on such a passionate intensity. We also know that these characters die at the end of the film (and the play). Such a strategy does not nullify the love of this couple. On the contrary, it intensifies the love between Romeo and Juliet, because a consequence of their deaths is that their love can be rendered pure and ideal. At least one commentator suggests that if the couple had lived happily-ever-after, they would most likely have become quite bored with each other, the passion of their love would have quickly subsided, and they would have become a typical bickering, frustrated married couple.

The fact that the film spares us all that – as does Moulin Rouge! and The Great Gatsby (and Luhrmann also adds that the lovers in Strictly Ballroom would most likely have ended up a somewhat boring and bored suburban couple!) – means that the couple’s love can be idealised: it is idealised because it is impossible, because it is forbidden, and that’s what gives it its intensity. If we were to remove all that, so that the secrecy of their clandestine romance was dissolved, then so too would the passion of their love most likely disappear. With the deaths of Romeo and Juliet, however, the idea of their passionate love can live forever.

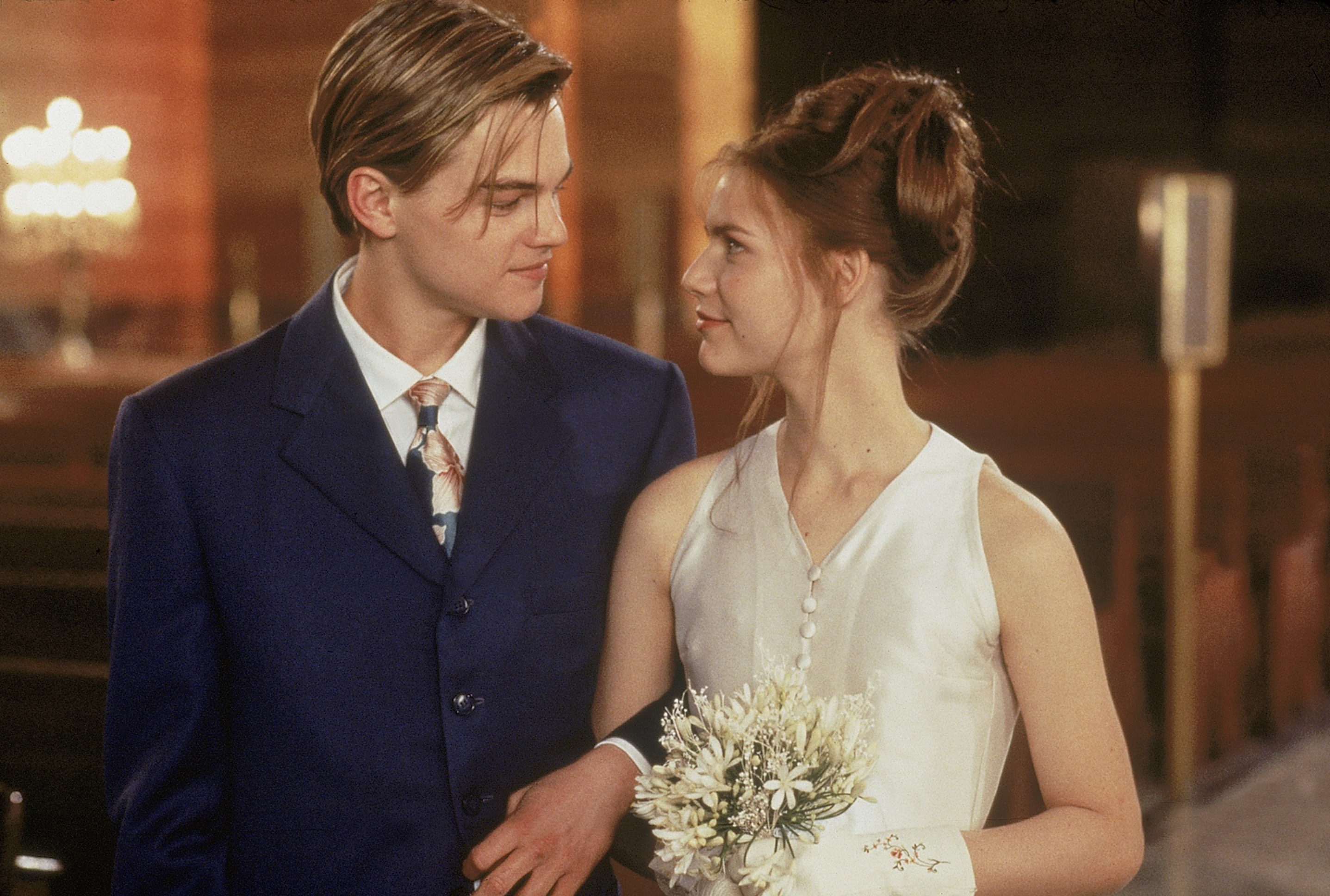

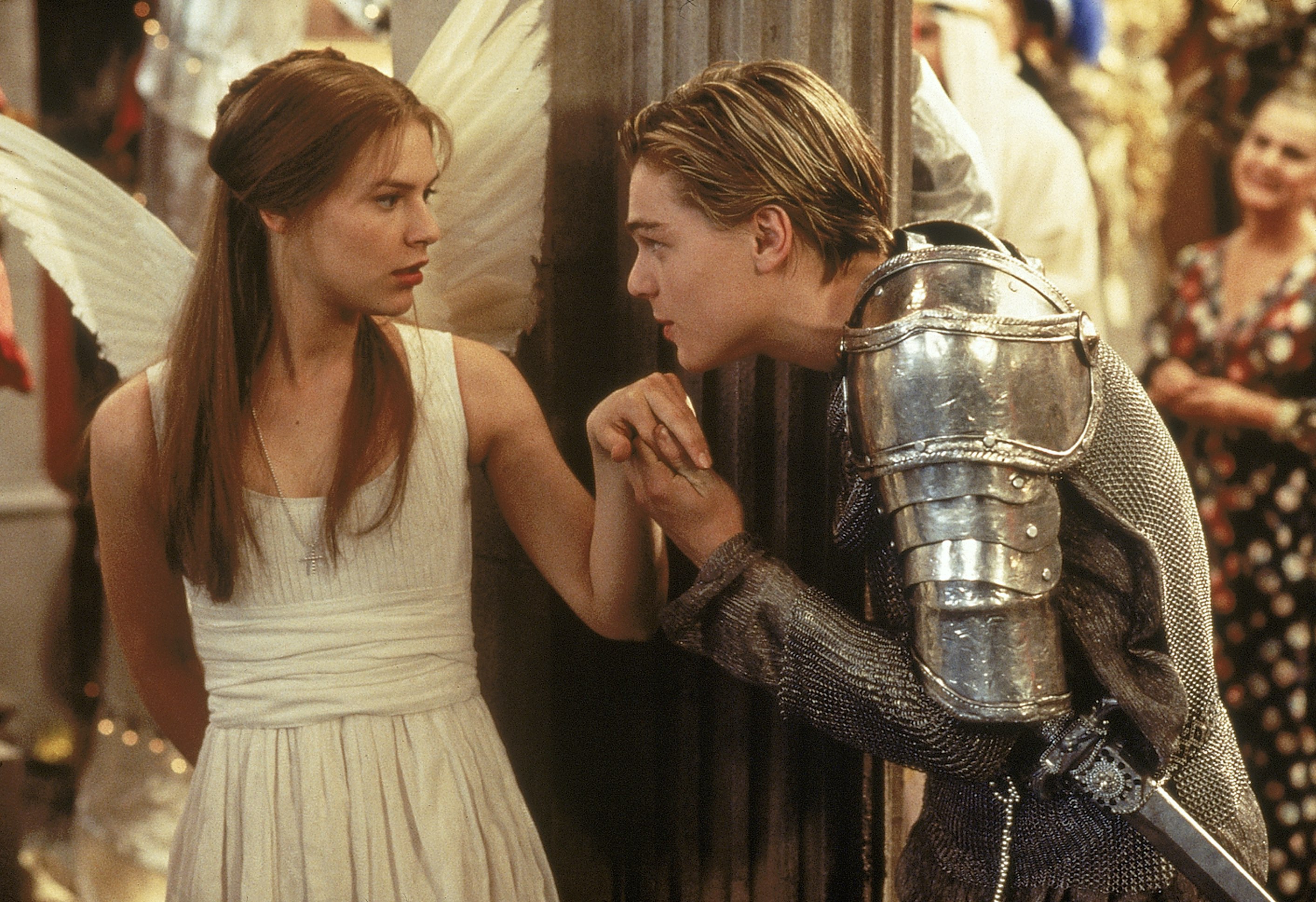

Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes in Romeo + Juliet (1996)

What lessons might we take from Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet? Why would Luhrmann adapt a play first performed in the 1590s? The play’s themes may well have been relevant back then, but in what ways does the play speak to contemporary audiences? Surely the whole notion of parents forbidding their children’s romantic attachments to members of rival families cannot be relevant today? Luhrmann is certainly adamant that the social prejudices practiced by parents today can be every bit as damaging to their children as those dramatised by Romeo + Juliet, but perhaps this misses the importance of the notion of love in the film.

Today, the thought that one’s love life might be determined by others – by one’s parents, for example – is certainly unacceptable: we want to be free to choose our own lovers! Thus, the kinds of social prohibitions dramatised by Shakespeare are ones that may no longer be externally foisted upon us. But we may well have enforced these kinds of prohibitions internally: if in the past a love match was a way of ensuring a family’s destiny, then today making a love match is a way of fulfilling one’s own destiny; love is today a matter of personal fulfilment. In other words, finding true love is a matter of achieving the sort of ‘self’ one wants. A love match, we would like to believe, will deliver a stronger and better sense of selfhood.

Thus we might consider that being-in-love today is a matter of self-formation or self-creation. We seem to be in a historical period where the sense of human self-fulfilment requires close companionship with another person. And don’t be surprised that this is actually a relatively recent phenomenon in human history: it has really only become a widespread belief in the last 100 years or so. French Philosopher Alain Badiou claims that this notion of modern love requires a sense of ‘being two’ rather than ‘one’ (and another French feminist, Luce Irigaray has written extensively on this point). But if this is the case, why do Luhrmann’s films so often end badly?

Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes in Romeo + Juliet (1996)

I think Luhrmann – well, I say ‘Luhrmann’, but it is well known that he is very good at being two, for his wife and co-creator is Catherine Martin, every bit as responsible for these films as Lurhmann is – is trying to claim that the barriers to human relationships based on love remain immense, whether this is a matter of old-world rivalries between warring families, or whether it pertains to more recent prohibitions against love enforced most strongly by destructive forms of modern capitalism: both Gatsby and Moulin Rouge! do their best to promote some sort of critique of capitalism in the name of love.

This is one of the reasons why the love between Romeo and Juliet remains so powerful: they have foregone any justification for their love except for the justifications they themselves give; this is a love they define and pursue on their own terms, in defiance of anyone else who might tell them otherwise, and even against Romeo’s own inclination towards the fair Rosaline early in the plot. They will define their love by themselves, together, in their own way. On those terms, romantic love becomes a remarkably courageous and dangerous thing to do. It is also this determination by the characters to define their love away from the impositions of their parents or any other social prohibitions that allows Romeo + Juliet to speak so directly and evocatively to contemporary audiences.

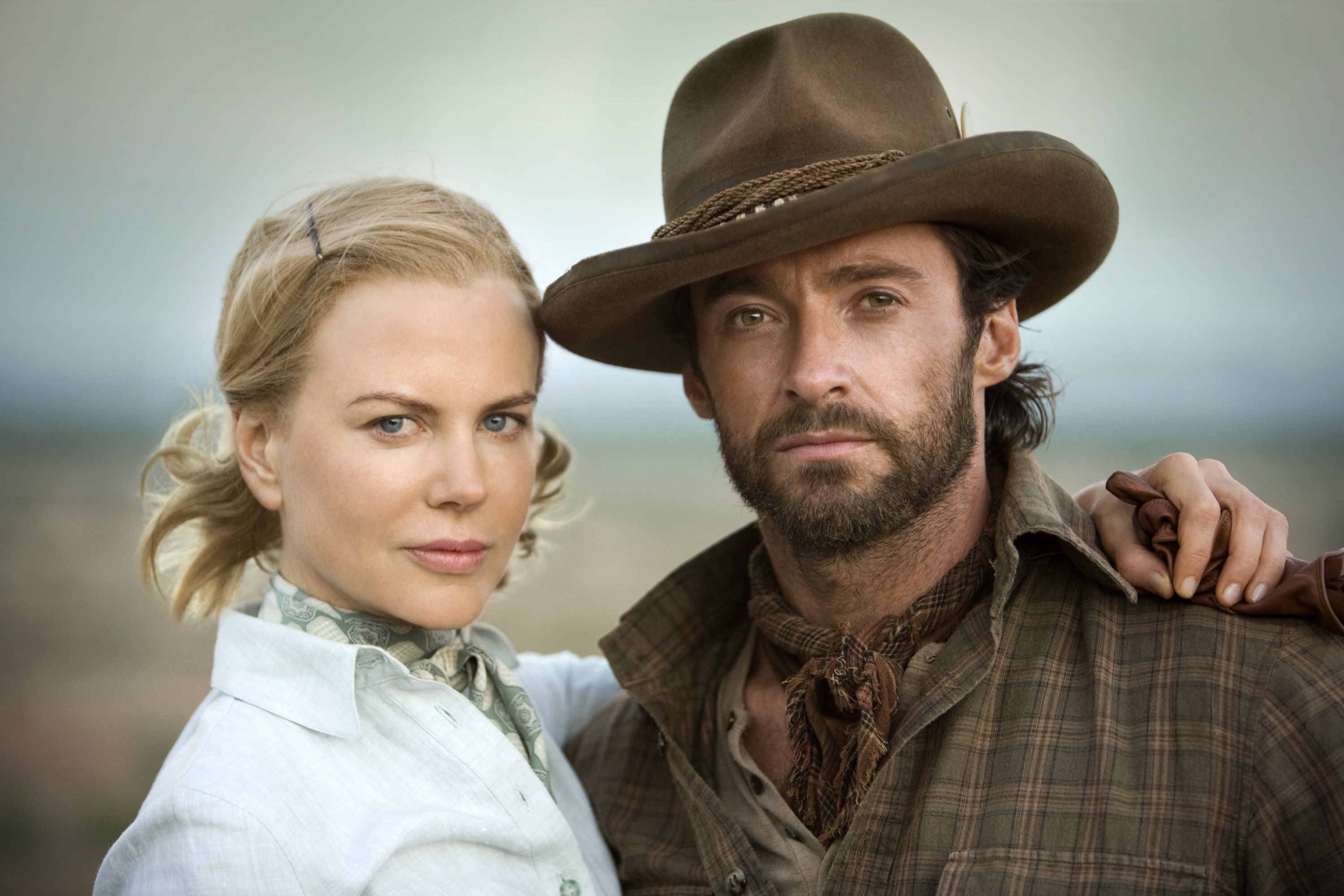

Hugh Jackman and Nicole Kidman in Australia (2008)

There is another of Luhrmann’s films that delivers a happy ending with a couple in love: Australia (2008). To win their love, Lady Ashley and the Drover (Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman) effectively remove themselves from the social worlds that have for so long restrained them. To that degree, they end the film happily-ever-after. Perhaps this is not the real ending of the film, however. The film ends when the mixed race aboriginal boy, Nullah (Brandon Walters), whom Lady Ashley has adopted, leaves the homestead in outback Australia so as to go ‘walkabout’ – that is, to embark on a journey of self-discovery.

In this way, Nullah is proposing a lesson for future generations: we must turn our backs on the social worlds that others have constructed for us and instead find ways of building social worlds that we can call our own, worlds that we can create for ourselves … Relationships based on love, if we are to trust Luhrmann’s vision, would be central to the creation of those future social worlds. And, indeed, those social worlds begin with relationships based on love, on ‘being two’ rather than one. The ideals of Truth, Beauty, Freedom, and above all, Love are aspirational aims voiced in Moulin Rouge! We could do a lot worse on Valentine’s Day than to celebrate those aims.

Hugh Jackman and Nicole Kidman in Australia (2008)

Richard Rushton is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Lancaster University. He has recently published Deleuze and Lola Montès (Bloomsbury, 2020) and is close to completing a manuscript on Modern European Cinema and Love for Manchester University Press.

All images are courtesy of Twentieth Century Studios.