In a follow-up to his earlier essay Glasgow on Film, filmmaker Gianni Marini travels across the Central Belt to Edinburgh to consider how the varied and historic architecture and impressive natural environment of the Scottish capital have been portrayed in cinema.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

A grey stone fortress sits atop a cliff. It is surrounded by a forest of spires, cupolas and tenements. The skyline is so dense and complex it is difficult to make out where one monument begins and another ends. Sweeping vistas of the city's centre show how the castle dominates the skyline. It's hard to capture such boldness on camera whilst bringing something new.

The Illusionist

The city is supernal, a host of domes, spires and steeples jostle towards the sky, above the rows of tenements. In Annie Griffin's Festival, the city can appear like a theme-park of monuments, with each building serving as a marker of humanity's desire to be remembered. Some filmmakers use this to draw a character's conflict into perspective. It puts them in touch with the past, offering historical context. Other times, it puts them in touch with their own history, offering catharsis. The variety of aesthetic styles, the gothic and the neo-classical, are all remnants of past settlements gathered together in a menagerie. This is most apparent in Sylvain Chomet's achingly beautiful The Illusionist (L'Illusionniste). It can make the protagonist appear like a titan, or a speck.

The Debt Collector

The same places change like sunshine into rain. In Anthony Neilson's The Debt Collector the city is simultaneously an imperial capital, where ancient monuments meet high art, and a medieval warren populated by junkies, prostitutes and thugs. The meetings, conversations, murder, sex and drugs that happen are the commonplace interstitial events familiar to city-dwellers. The narrow confines contextualise the drama - forming a multi-dimensional game of snakes and ladders.

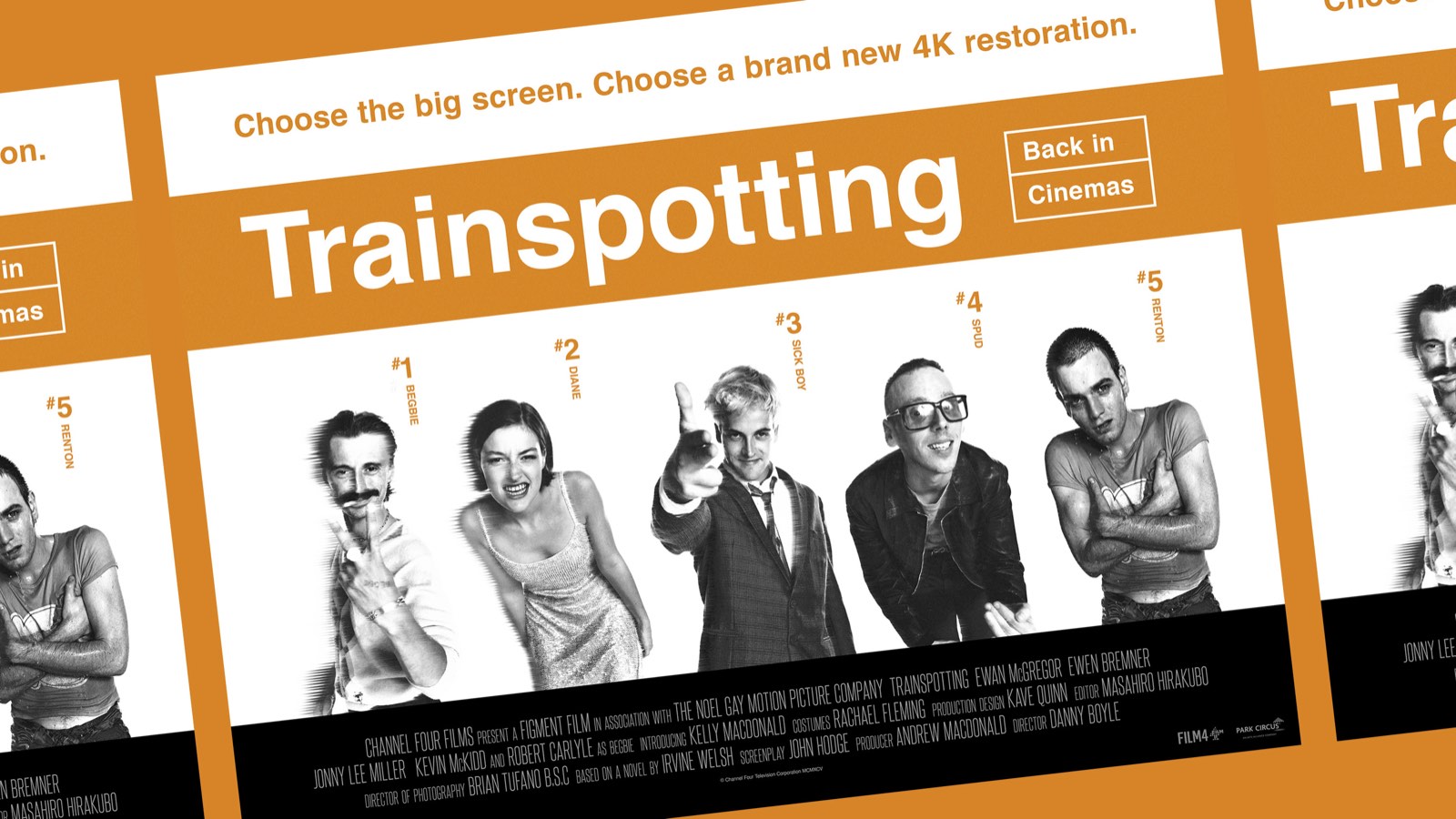

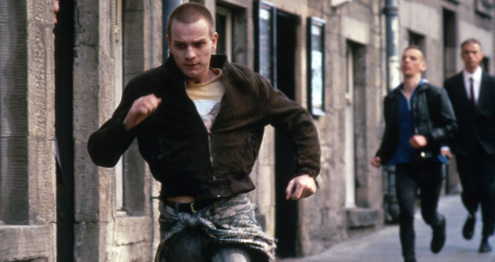

Trainspotting

The filmmaker weaves the strands of life together and the wynds and stairs lead us to the chthonian city within the city. Like in David MacKenzie's Hallam Foe, Edinburgh can appear as though it is one monstrous castle, like Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast, populated by different peoples on different sublevels, forming different sub-cultures. The rise and fall of the city's steps form the backbone to tales of human frailty. The stairs cut across the frame. They form passages from one world to the next, a portal through which elements of the city's underbelly can escape into the fabric of the civilized capital. The forgotten and ignored invade the austere beauty of the city in Trainspotting, bringing chaos with them. We begin to see the city from a different perspective. Not drifting above its skyline of spires but down amongst the cobbles and corners, where the city envelopes you like an immense gothic asylum. Protagonists lose themselves only to emerge from the nooks and crannies.

Edinburgh's architectural monumentality is matched by its natural backdrop. Arthur's Seat, an outpost from which to survey the city, offers a view that allows us see how, over time, Edinburgh has expanded, shifted and continued to build monuments to memorialise its past. It is from this vantage point that we see how the city has built upon itself and how Edinburgh's multiple dimensions intersect with each other. How the walls look, like people's faces, depends so much on how they are framed. In rain or in sunshine, close or far away. The city can look unreal and beautiful, but also real and distant.

You can see more of Gianni's work at: www.giannimarini.com

Browse our Scottish Interest collection